In 2016, Egg Farmers of Canada (EFC), which manages the country’s supply of eggs, decided to phase out conventional cages in favour of housing requirements that give hens more space to perch, nest and scratch, either in larger enriched cages equipped to accommodate those instincts, or in cage-free barns.

But for egg farmers, the move toward cage-free systems can drive up costs, especially because the practices are relatively new and not as well understood as conventional cages. For example, it can be harder to control the temperature and air quality in dustier cage-free barns. It’s also harder for farmers to manage birds that are not in cages, so the risk of hen injuries and cracked, lost and dirty eggs is higher. “That represents economic loss for egg farmers,” says Helen Anne Hudson, Director of Corporate Social Responsibility for Burnbrae Farms, one of Ontario’s largest egg producers, located in eastern Ontario.

“Most of Canada’s 27 million laying hens will need new homes over the coming decade or so.”

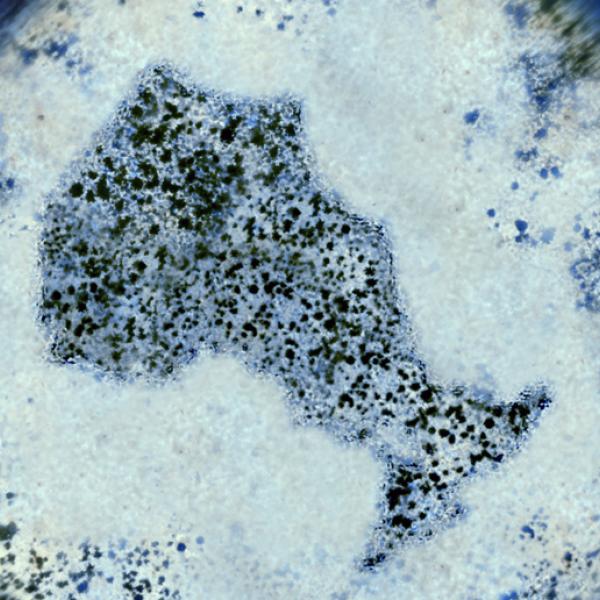

The stakes are high. In Ontario alone, more than 400 egg and pullet (young hens) producers generate nearly $400 million in sales each year. The new requirements mean most of Canada’s 27 million laying hens will need new homes over the coming decade or so.

Tina Widowski, EFC Research Chair in Laying Hen Welfare and a researcher at the University of Guelph is working with the industry to help ease the transition. CFI funding allowed Widowski, who is an animal welfare expert, to purchase equipment to track and analyze how different housing systems would impact hens. Her data helped inform development of a new Canadian Code of Practice with required standards of care for laying hens. For example, her work contributed to the confirmation that hens strongly prefer to lay their eggs in a closed-in space, so having a designated nesting area promotes calm “settled” egg laying behaviour which contributes to good hen welfare.

Making sure the code of practice is based on top-quality science is good for the birds and good for egg farmers. “It reflects the industry’s desire to provide the best care they can for their hens,” says Hudson.