Youth and research: a promising future

Young adults are navigating a rapidly changing world where climate change, social justice, and the economic and societal aftermath of the pandemic will be the defining events of their youth.

But with change comes an extraordinary opportunity for this generation to alter the trajectory of humanity, embrace a more empathetic value system and define their own futures.

Research and discovery will be their beacon, and a way for them to contribute to a world in transformation.

From advancing renewable energy sources, to building a more inclusive society to developing powerful new medicines that tackle some of our deadliest diseases, research promises the possibility of a future that can be profoundly different from the past.

The Canada Foundation for Innovation invests in the research labs and equipment that give rise to that potential, and engages young people in research by asking “How can research forge the future you want?”

A conversation on the results of a survey of the attitudes toward science of 18- to 24-year-olds

I am very pleased to be joined today by Mona Nemer, who is the Chief Science Advisor for Canada, Specialist in Molecular Genetics and Pharmacology. She was the Chair in cardiovascular cells and cardiac formation and function. She is a knight in their order of merit of France and a member of the Royal Society of Canada.

Also, we are honoured to have Rémi Quirion, who is the first Chief Scientist of Quebec, former professor I guess, everyone is still a professor of psychology and psychiatry at Sherbrooke and at McGill, and Director of the Douglas Research Institute, Assistant Dean in the Faculty of Medicine at McGill, and the first Scientific Director of the neuroscience institute.

Together, we have somebody who has studied the heart, and someone who has studied the brain, who have put together the heart and the brain and come together to treat a subject that is really important, and that is youth. It is the 25th anniversary of the Canada Foundation for Innovation, and the 100th anniversary of Acfas and together we thought we’d celebrate our anniversaries or birthdays, not by looking at the past and bragging about the great things we had done, or thinking about what we could have done, but looking at the future, and the future is young people. Together, we did a survey of young people and asked them how they felt about science, and how they felt about science in the future.

They, indeed, are our future, and the best part of the survey was that 78 percent of the young people like science. They believe that it might be a great career for them. Knowing that they think that, how would you encourage them to continue and carry on in that thought, because they have ideals? They want to change the world and solve the great problems of the United Nations. Yet, every time I listen to a graduation speech, they say, and you young people are going to go out in the world and correct all that the adults have wrecked for the last 100 years. What a weight to put on their shoulders. How do we get them to feel filled with hope and realize those possibilities in science?

Well, you don’t have to both answer at the same time.

Mona Nemer:

I mean, I’m delighted that so many of the young people want to go into areas of science, because I profoundly believe that science will provide the tools to better this world and to overcome some of the complex challenges that we have, from climate change, people migration, food security, not to mention, of course, health. I think it’s upon us to help the young people by providing them opportunities to fulfil their dreams by equipping them with what they will need in order to tackle all of these problems. There are just so many different ways by which they can contribute throughout their life, whether while studying or later on in their careers. I think we need to facilitate this, and it is even selfish for us, because it’s in our own best interest for them to take on these challenges.

Rémi Quirion:

Yeah, and maybe I could add a little bit here. I must say that when I saw this data in the survey, I think we are very, very pleased and very fortunate that so many young people in Canada that are interested to do careers in research or to think about science. I think the — you say there was a lot a pressure on their shoulders, but I think there is a lot of pressure on our shoulders in the sense to make sure that we provide them with the right support, so that they could fulfil their dreams to do a career in science and research in whatever field that they want. It is for us that we must find ways to better support them in what they want to do and what they want to achieve in research and in science. We are not there yet. We still have challenges in Quebec and in Canada in that context.

O’Reilly Runte:

Yeah, our work is never done for everybody. There are good news pieces that happen. Ten years ago, we did another survey, and in that survey, we found that really young women — like at age 8, felt science was great, but by the time they were 12, they no longer wanted to study science. Since then, there have been coding camps and Let’s Talk Science, and women for science, and the good news in this survey is that young men and young women equally want to pursue careers in science, but how do we make it so that they want to when they are getting to graduate school, when they’re getting to college? How do we keep that — the wind in their sails?

Nemer:

I think there is — this is a collective issue for society and both men and women need to embrace it and do something about this. You mentioned about girls not wanting to do science and math as well when they’re 12 or later. For a long time, it was viewed as uncool to be doing science. Scientists were viewed as these nerdy, non-social human beings, which is everything — it’s just so far from the truth, of course.

I think that we have to stop this caricature of what scientists look like or not. I think there are positive models and empowering the young generation throughout their development to continue embracing science, technology, math, is very important and helping them along, whether it’s at school or later. Putting in front of them role models for the different types of careers actually that people can achieve. They’ve studied science and many of them will not involve being a full-time scientist in any particular job. I think this diversity is very important, but it’s also important to make sure that collectively we’re not perpetuating biases and perpetuating stereotypes that are counterproductive.

Quirion:

Education, scientific literacy is critical. Roseann, you mentioned college and university. It has to start in primary school, and high school. So, basically, we have to make sure that we improve teaching of science in high school. We change models, we have role models there as well, especially for the ones that may not be so convinced about science, about research, the ones that goes on the weekend for Expo-science, scientific exhibit and all that, these are the ones that are already onboard, but it’s for the other ones that we have to make sure that we do not lose them, so we have to provide them with incentives to have an interest, in an interesting type of way of teaching science. We have not done that so well in Canada. We can certainly improve on that front, but we’ll have to start also in the faculty of education in university to change the way we train future teachers.

Nemer:

Literature and music are not seen as niche for only musicians and literary types, and science should not be viewed as a niche for only a small segment of the population and everyone else not having to deal with it. We need to normalize both the learning of science and the using of science throughout society.

Quirion:

Not to lose a good crisis. We had a huge crisis with the pandemic — never ending pandemic, but science has never been as much in the forefront, so to generate interest in the population, society, including in younger generation. We have to make sure that we do not lose that interest by changing the way we do things.

O’Reilly Runte:

Shouldn’t we also be thinking about science not simply as a career, but science as important for being good citizens for being participating members in society. We see people voting based on what they think is good science or not good science. Should we not be thinking that science is important not just for a job but for being a good citizen?

Nemer:

Yeah, we’re all users of science every day. If we want to use something, we need to know a little bit about it. Using science is actually very beneficial. The young people, I think, started getting interested in science because of the environmental and climate challenges and issues, and I think that they perceive that science and technologies are critical, both for solutions and also as a basis for monitoring, for improving, for keeping politicians and society accountable. I think it’s also the use of science that can and should motivate learning science and knowing a bit about science.

Quirion:

One more example that guided political views a bit more is Jérôme Dupras. Jérôme is a member of Les Cowboys Fringants, a well-known group in Quebec but worldwide in the French-speaking countries they are very well known. Jérôme at the same time is a Canada Research Chair in Environmental Science, and he is doing fabulous things in Quebec, for example, in terms of biodiversity and all of that. When he gave a scientific talk, he starts by the science, the scientist talking about environment, about biodiversity, then finishing by his career, the dual career as part of a very popular group. I don’t know how he does that, he’s able to do both while having three kids, how he (inaudible), but this type of person so he’s still quite young, so can be a model also for the younger generation. I guess you can be a good musician, but at the same time you can do science. Not everyone can do that, of course, but I think we need to have some of these guys much more visible on the national scene.

O’Reilly Runte:

That’s a really great positive example, because I was only thinking of negative examples, like H. G. Wells when he announced War of the Worlds, and everybody thought there were really little green men from Mars going to come on Earth, and they actually had traffic jams. People ended up in the hospital. The U.S. Military were out on the — trying to save the citizens of the country. It’s — if people stopped and thought and measured the possibilities in a scientific way, using the scientific method — Mona, you’re an expert at that.

Nemer:

Well, the scientific method, I think it’s super important. We often talk about science literacy and the people think that we want to give courses of biology or physics to everyone, but that’s really not the point. I think the point is to understand how science works, what’s the hypothesis, how do you go about doing it, how do you reach a conclusion, and how do you evaluate the strengths of your conclusion versus the data that you’ve collected. I think that’s something actually that can serve us in our everyday life, including for people who are doing — making policy decisions, and people who are looking at all sorts of societal issues and activities and solutions.

I think that science is an important tool, and the scientific method needs to be well understood by everybody. We talk about numeric literacy. We talk about financial literacy. We don’t talk enough about science literacy, which in many ways underlines also the other two.

O’Reilly Runte:

The other two underline it.

Nemer:

Yeah.

Quirion:

Also, maybe again, it’s having an example, but also that saying and showing that science is fun. Science could be really exciting and really fun, because often they will see the side that is kind of drab, and it’s not like that at all. When you are in your lab, doing research with your students, and then you have a new finding, you’re the first in the history of mankind in a sense to see that. Then, after that, takes 10 years to come visit only when it’s important. That’s another part of the deal, but it’s really fun to do science, and you’re all your own — you’re an entrepreneur in a sense. You’re creating new things, and we don’t show that enough in our society.

Nemer:

Well, it’s discovery. It’s adventure. It’s constant change. Sometimes change isn’t well understood.

Quirion:

But it’s a lot of fun, so that’s — and it’s not linear also, because sometimes you think it’s very linear, you end up be a prof at a university, and you retire maybe thirty-five years later. No, it’s not the way it goes (inaudible). We have to show that more often, I think.

O’Reilly Runte:

I think the pandemic has offered us quite an occasion to tell people how important science is. I remember going to the Gairdner Awards, and there was a woman from Texas that won the award, and she said that for 13 years she had considered herself a failure, because she was looking for a rare chain that caused a specific disease. After 13 years, she eliminated ones, but she never found it. When she did find it, she got the Gairdner Award. She was nominated for a Nobel Prize. She said finally, “I’m a success.” I think every year she was a success. Every year she got us closer to the solution. In the pandemic, because scientists were able to come up with a vaccine so quickly, it wasn’t a miracle, it was many years of research.

Nemer:

It was many years of research, often in unrelated areas that converged to give us the vaccines, or to give us the antivirals that we have. Again, back to what Remi was saying about non-linearity, it’s like you don’t know where the next solution is going to come from. It’s often a convergence of many small and big discoveries and advancements that were made sort of in parallel by different people that give you these eureka moments.

Quirion:

Yeah, and I think it shows the importance of investing in the basic research, in fundamental research in all kinds of fields, because you never know where will be the next big challenge of our society, or you don’t know where will be the next big breakthrough in terms of science and research. I think for good scientists, you almost also need to be somewhat of an artist. You need to have a nose as well. The data, when you get the data, what is evident probably is not that interesting. It’s kind of the side — data aside, you don’t understand. That’s probably where you need to go.

O’Reilly Runte:

I think you’re quite right. In the interdisciplinarities is really quite interesting and can be so unusual.

There was an article in Science magazine by a young woman who studied in Canada quantum, and she loved Victorian science fiction, and so she actually has invented a new field that she calls Steampunk Quantum. I can’t explain it, but she did a really good job in the science magazine, which is something that scientists aimed for years and years to get published there, and she’s just a fledgling professor. I think that you’re quite right, both of you, that the discoveries come, not necessarily where you’re looking but from crossings of disciplines and new ideas that come by researchers coming together across the country and around the world and across disciplines.

Nemer:

Also, making it easy, the access to the new knowledge so that it can be mined, and that people who are not thinking the same way as us can see what we have overlooked, and this is, as Remi said, where most of the more interesting things lie.

Quirion:

You’re, in a sense, of course we’re part of Canada, but as a scientist, you’re kind of part of the world, and it seems corny to say that, but it’s a reality. You’re a collaborator from all over the place, all over the world. That’s also, you meet all kinds of very, very interesting people, and I think that’s one of the benefits of science as well that we don’t talk about enough.

O’Reilly Runte:

You’re both such incredible role models for all of us, but particularly for young people. In your careers as you transition from scientists — but you’re still scientists, I know Mona is still working in her lab, but she takes on extraordinary additional responsibility. How do you see those two careers coming together, and is that something that can inspire young people that if they go to the lab and start their career there, they may end up doing something entirely different?

Nemer:

There’s no question that you never know what the future holds for you, but many of us — I’ll certainly speak for myself, we take on responsibilities because of our love for science and our love for the future generations, and we just want to make sure that we leave for them a system that is — a solid system where they can prosper and where they can make their own contributions. We’ve benefited from what others have done before us, and we want to do our share to leave them a good system. It’s sort of the reason why we do science, for the love of science, and why we get involved in the management of science, because we just want to make sure that it stays on the right tracks.

Quirion:

I’m sure that Mona has the questions as well I have and still have after many years, still have the question, how do you become a Chief Scientist? My answer is that I have no idea. Don’t plan for it, it will not work. At the same time, of course there is frustration on both sides, but the type of job we have these days that there’s something new every day. You learn something new every day. It may not be the result of an experiment, but it's something new, people, different type of people, different fields. That’s, for me, the stimulation to continue in the job I have now.

O’Reilly Runte:

Both of you are Canadian and Quebec Chief Scientists, but you work with Chief Scientists around the world. I get from people two things. One is we have to be really good at whatever area of science they’re in, in Canada, because we never know — we can never trust other countries, and we would have to be very insular. At the same time, there are groups saying there is no way that we can solve big problems of the world unless we work globally and work with other researchers. Is the truth somewhere between the two, or where would you — which side of the pendulum would you swing?

Nemer:

Take the pandemic, if we wanted to be — to use only the vaccines that we generate in this country or the knowledge that we generate in and only in this country, I don’t think that we would be where we are now. We’d still be waiting. These big challenges, whether it’s pandemics, whether it’s climate change, whether it’s the application of new technologies to so many areas, we just have no choice. We have to collaborate. There is an impetus to collaborate, to go faster in terms of finding the solutions, but science is also a way to unite people, to basically transcend all the divisions, because there’s more that unites us than divides us, and we have to maintain this way of being able to communicate and to dialogue with other countries when other means of communications break down.

Quirion:

I fully agree, and I just say that science diplomacy opens doors, science opens doors. I think we have to use science to — and work globally to try to solve the problems of the world. It’s a big challenge. We cannot do it — only say, well, Canada will do this thing and not collaborate with the rest of the world in science. It doesn’t make sense.

O’Reilly Runte:

I think both of you have opened doors, opened minds, and opened hearts, and I think that it’s the young generation that’s the hope of the future. You’ve given them hope, hope in a career in science, hope in the capacity of science, and even in the joy of science. I can only say thank you to both of you so much for this wonderful conversation. It’s a privilege to talk with you.

Quirion:

Thank you very much.

Survey highlights

The good news is that science matters to the majority of these young Canadians. While there is work to do to connect with and inform those who are more science hesitant, it is encouraging that the results suggest many in this demographic follow, trust and even promote science.

| 70% | said science can be relied upon because it is based on facts and not opinion |

I believe that science is what we should base our opinions on. If we can't trust science, who would we trust? … I hope more young Canadians will look towards science to guide their decisions.Anonymous survey participant

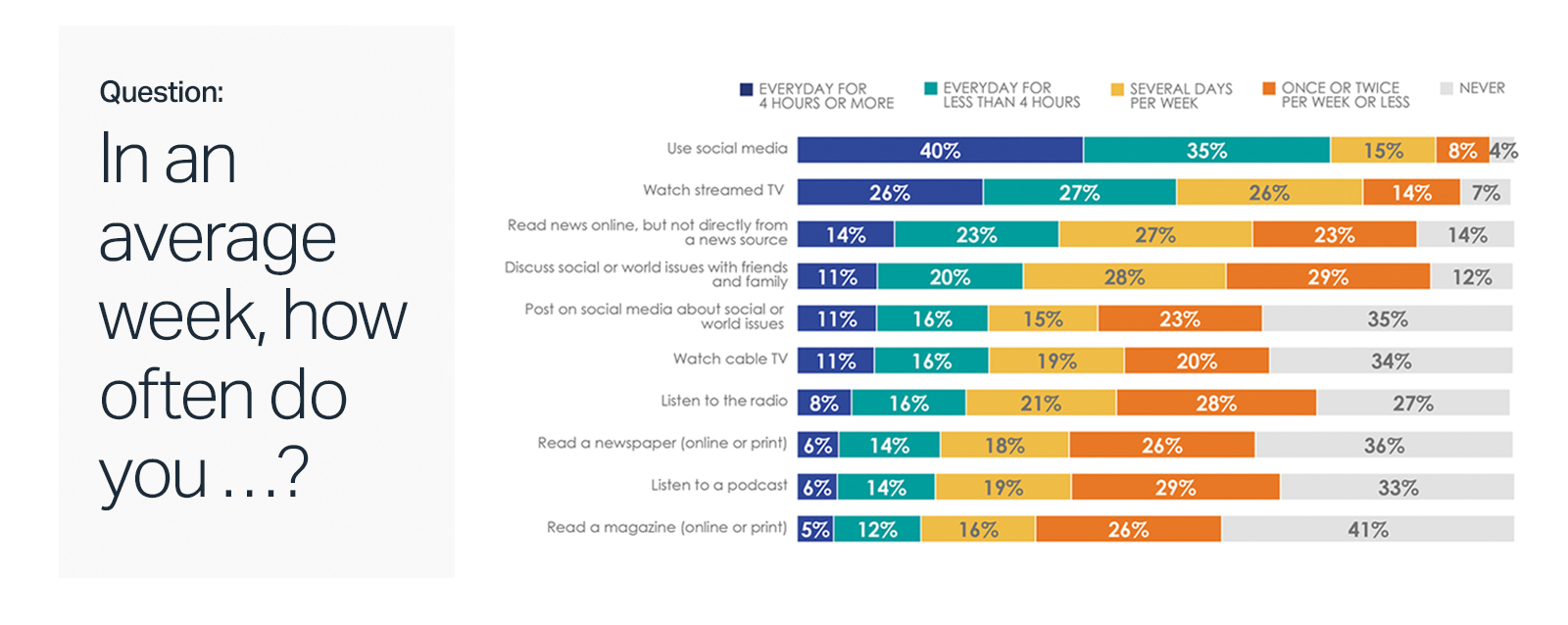

Where do young adults get their information?

But there are areas we need to work on…

| 73% | Respondents reported following at least one social media influencer that has expressed anti-science views*

|

Overall, the survey made clear that young adults are navigating an extremely complex and diverse information ecosystem where they are inevitably exposed to fake news and anti-science information. This presents an increasingly difficult challenge for science communicators and educators.

As a follow-up to the findings of our survey, we invited stakeholders from across the country to a virtual event to reflect on the role of educators in promoting science literacy; the current state of science communication to build public trust; and, the skills in science and technology that will contribute to the Canadian economy.