If practice makes perfect, how great would it be if employees could take multiple visual tours of their new workplace before setting foot in it? Especially if that place happens to be a cave, a tunnel or a mine.

That idea may soon be a reality thanks to Alessandro Navarra, a researcher and professor at McGill University’s Department of Mining Engineering, who is leading a new applied research project to improve operations planning for mines and mineral processing plants. He leads the department’s Mining System Dynamics Group, where he conducts innovative research for people who design and operate mining and metallurgical facilities, as well as to train mining engineering students. His work involves using virtual reality (VR) to serve the mining ecosystem in a highly educational way. And his new VR tools could solve the issue of access to mines and metallurgical facilities for training and development of new operating procedures.

Navarra and his small team use state-of-the-art equipment funded by the CFI. This includes two Vortex Edge Max simulators developed by CM Labs, a Montréal-based company that specializes in simulation training. The team also used Unity, a well-known, development platform, to design VR simulations. With it, they will produce graphical simulations and combine them with sensor networks to create digital twins of mining environments. Those twins are then integrated into control systems that help users study the environments, make general recommendations in real time, and identify areas where more detailed inspections will be required.

VR simulations allow workers to practice handling different scenarios and be better prepared for any contingency. “Process automation and artificial intelligence are already having a major impact on our role as humans in the mining ecosystem,” says Navarra. “We want to provide additional support by leveraging VR.” Navarra and his team are keen to create a range of simulation-based support for mines and metallurgical plants, from the initial construction phase to the continuous improvement of operations.

VR in education

Nasim Razavinia, the associate director of academic programs at the Faculty of Engineering, is also excited about the educational applications of VR: “Engineering students often can’t gain access to mineral processing plants, so virtual reality tools are proving to be a safe and effective way to learn and integrate theoretical knowledge. We can simulate inaccessible environments and difficult scenarios to help our students improve their diagnostic and problem-solving skills.”

New VR technologies play a crucial role for universities, providing interactive training for the students who will design the mining and metallurgical facilities of the future. They’re also useful for operators in the field.

A virtual tour of a concentrator

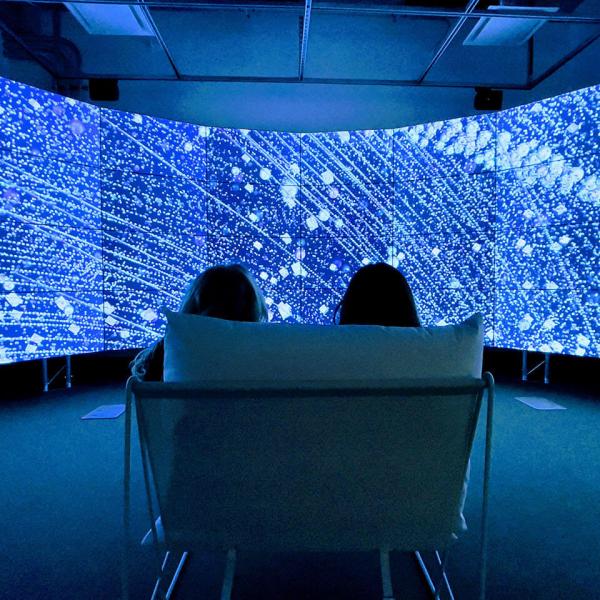

The Mining System Dynamics Group is currently studying a very specific operational stage in the mining chain: the commissioning and operation of concentrators, which separate ore into concentrates and tailings so that the latter can be sent to treatment facilities. That’s where virtual reality goggles come in.

Navarra’s team wanted to recreate the experience of working with a concentrator as realistically as possible. To do this, they visited the LaRonde metallurgical complex in Quebec’s Abitibi region.

Navarra worked with Blaise Hanel, a video game developer, to program and finalize the VR software, making sure it could produce reliable computer-generated images and information. “With the technologies we now have in the lab, we can offer a VR experience that is more lifelike than ever before,” says Hanel. “We received positive feedback from the people who tested the software, and we used their recommendations to improve it.”

Social and environmental objectives

Says Navarra, “I plan to use my expertise and that of my colleagues to keep delivering better simulations across the mining chain, from excavation to metallurgical processing. That’s how we’re preparing the next generation for the realities of the job. As in all primary industries, there are opportunities to modernize, and we need to seize them to foster a more strategic approach to Canadian innovation.”

While the tour is currently available in English and French, Navarra would like to make it available in Indigenous languages. “That way, we could offer a direct tour experience to the communities living where the mining and metallurgy industry is largely based.”

At the same time, Navarra is planning to broaden the scope of his team’s educational innovations to other stages of operations, such as drilling and blasting, and especially earthmoving at tailings facilities, which has big implications for the environment.

This initiative is driven by Canadian values, including environmental stewardship, the involvement of Indigenous Peoples, and the improvement of living standards in rural areas. As in all primary industries, there are opportunities to modernize: mining 4.0, forestry 4.0, fisheries 4.0, etc., and we need to seize them to foster a more strategic approach to Canadian innovation.